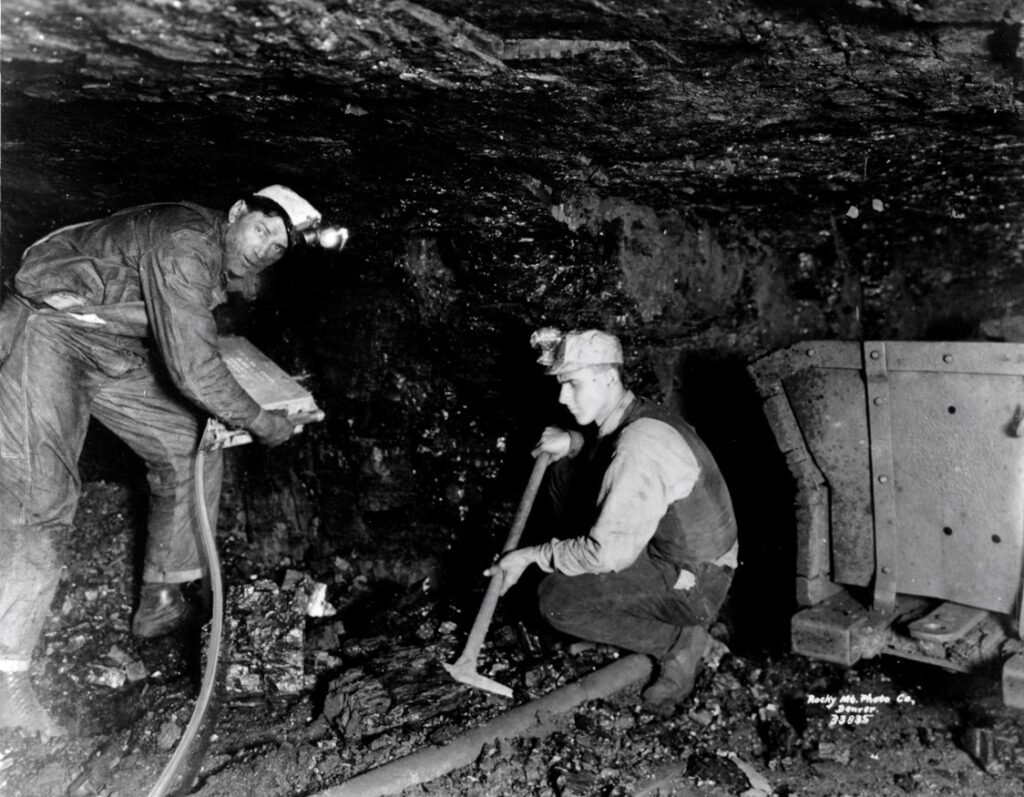

Figure 1 Men at work at a Lafayette coal mine, 1921. Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library Western History Collection.

Though gold and other minerals put Colorado on the map, coal fueled those mining endeavors and went on for as long as the hard rock mining continued. Coal mining occurred all over the state, with coal camps in the southern fields around Trinidad, in the northern fields near Lafayette, and far in the mountains in Crested Butte and places like New Castle. There were even coal mines in Golden, Colorado not far from where the Colorado Railroad Museum is located today.

Coal mining was a dangerous job, and rather than being paid for the workday, miners were paid for the quantity of coal they were able to gather. This meant that any work undertaken to stabilize the mine, such as timbering, was considered dead-work and was unpaid. Colorado coal miners often had to decide between their safety and their livelihood.

Figure 2 Miner at work in Kubler Mine, Gunnison County, Colorado, 1913. Note the timber used to support the roof of the mine. Photo courtesy Denver Public Library Western History Collection.

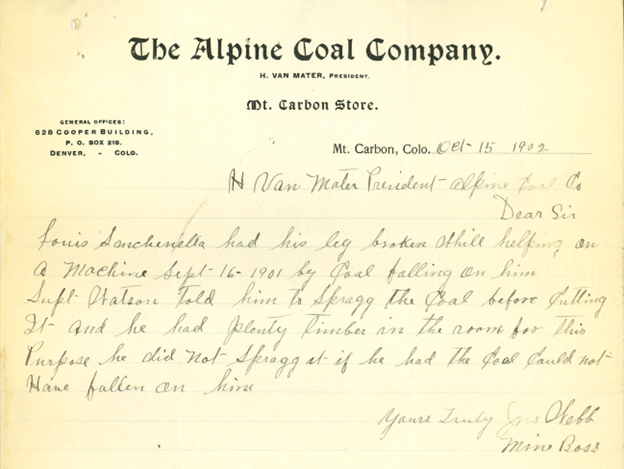

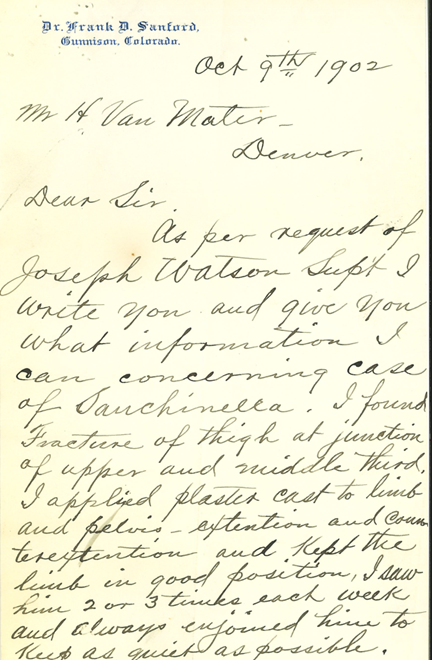

In the Museum’s collection, there are documents detailing an accident that the Alpine Coal Company claimed was due to a miner’s failure to place a sprag, a wooden beam used to prop a section of coal up to stabilize it. It happened at the Alpine Mine in Gunnison, Colorado, in September 1901. A piece of coal fell on Louis Sancinella/Zancinella (the spelling differs in the letters) breaking his leg. The documents in the collection include letters from a doctor who treated him as well as letters from the Alpine Coal Company officials regarding the accident. The documents all agree that the miner who was injured was the one responsible for the coal falling as he did not sprag it, despite being instructed to do so.

Figure 3 Mine boss account of Sancinella’s injuries, 1902, Colorado Railroad Museum collection.

Figure 4 Dr. Sanford’s account of the injuries sustained and the demeanor of the patient, 1902, Colorado Railroad Museum collection.

Even without the balancing act of dead-work versus livelihood, coal mining in Colorado was extremely dangerous. Between 1884 and 1912, Colorado coal miners died at twice the rate of the national average, with 1,708 men and boys perishing on the job. Mines in the state had a high volume of methane gas and scant safety regulation, which led to numerous explosions. The mines also were at risk of flooding, which is what happened in the White Ash Mine in Golden in 1889, when an undetected coal fire from an abandoned mine shaft broke through the active shaft and water from Clear Creek came rushing in. All 10 boys and men working that day were forever entombed in the mine.

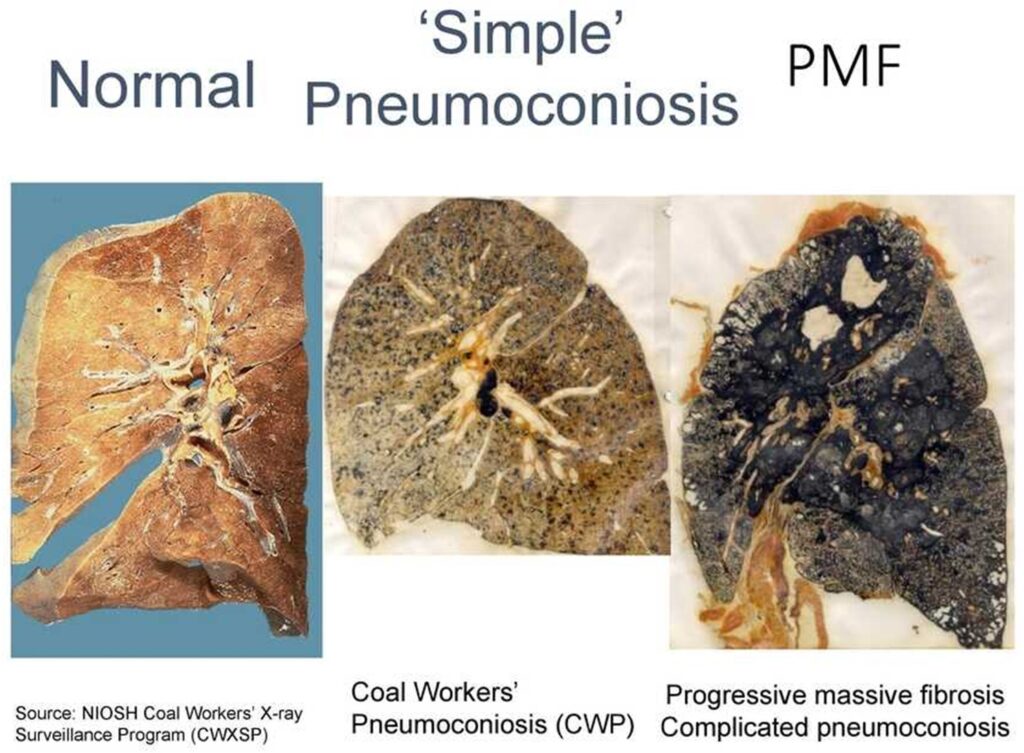

Even if miners were lucky enough to survive the immediate dangers of coal mining, they often breathed in harmful dust and coal particles that were released in the air during the mining process, causing black lung, a disease that weakened the lungs and led to painful deaths over a period of years.

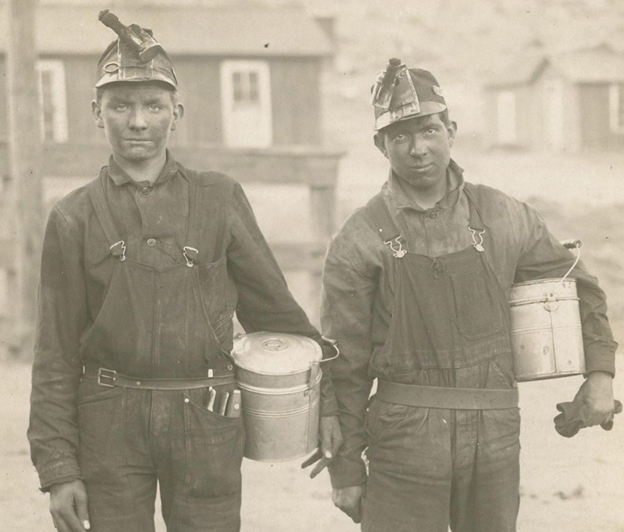

With all these dangers in mind, who were the boys and men that decided to work in coal mines? Mining for coal was not a glamorous job, and the miners sought to make a living, knowing they would never strike it rich the way that hard rock miners sometimes did. It often depended on the region, but men of many races and ethnicities became coal miners. This was especially true in the southern coal fields. Immigrants from different European countries made up the majority of coal miners in the southern part of the state, but there were also Black and Latino men that worked the mines and faced rampant discrimination in the process.

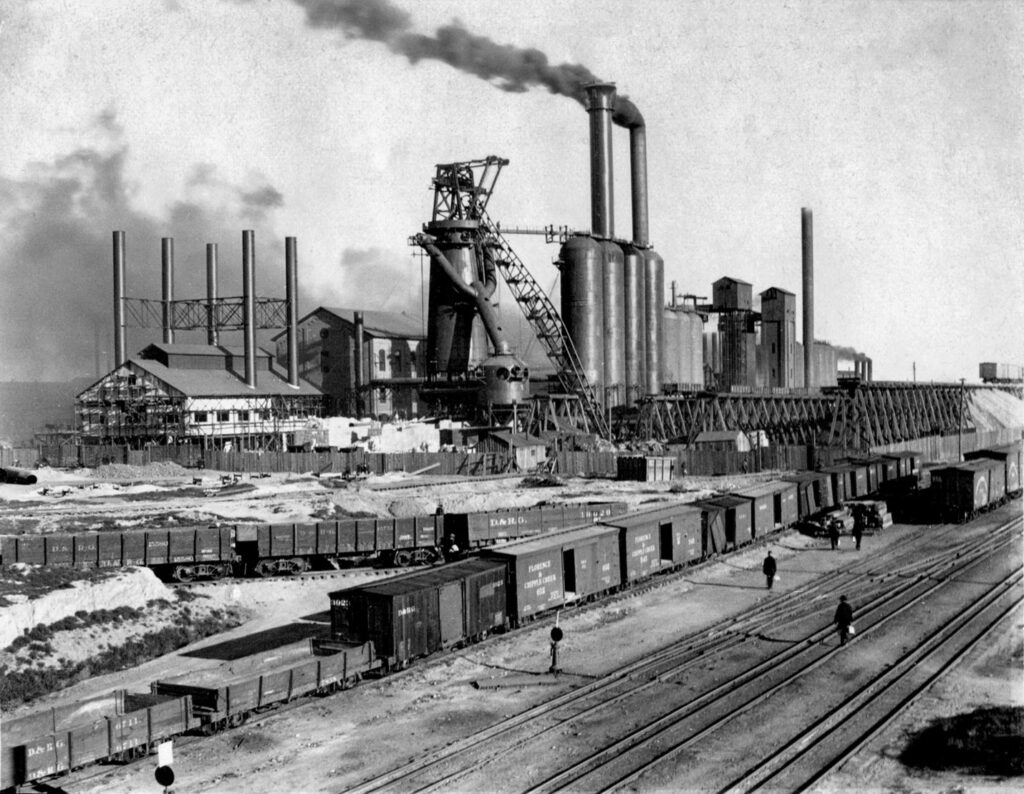

Coal’s success as a resource was dependent on its relationship with railroads. Coal needed a mode of transport to get to market, and railroads needed coal to fuel their locomotives. Many railroads expanded their lines based on where the coal mines were located, including the Denver & Rio Grande under William Jackson Palmer. Palmer recognized the significant role coal would play in the railroad’s development, and in addition to opening coal mines and expanding his lines on them, Palmer also created the Colorado Coal & Iron Company in 1880. This early firm later merged with John C. Osgood’s Colorado Fuel Company to become the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company or CF&I. This company created a vast steel and coal industry in the American West with the steelmaking center in Pueblo, Colorado. This relationship between coal and the railroads put Colorado on the map, encouraging railroads to connect from all across the nation. Pueblo’s steelwork center became known as the “Pittsburgh of the West.”

Figure 6 William Jackson Palmer, founder of the Denver & Rio Grande Railway in 1870.

Due to Pueblo’s role in the coal and steel industry, and its location near the southern coal fields, we are featuring a recipe today that would have been served in the coal mining towns around Trinidad. Women’s days in these company towns were often longer and harder than their coal miner husbands’. They had to wake before everyone else in the household to prepare both breakfast and lunch, at the same time, for the household and the miners. According to Rick J. Clyne in his book Coal People this included not just the husband, but any boarders that the woman would have taken on as well.

Figure 8 Coal miner family taken during a strike against CF&I in Ludlow, Colorado. This strike culminated in the Ludlow Massacre of 1914. Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library Western History Collection.

A coal miner’s lunch pail was essentially a bucket that had separate compartments. The bottom compartment held water, sometimes with fruit—which not only preserved the fruit but left space for the dry goods above— while the upper compartments contained the food. The lunch pail had to contain all the food and water the miners needed during the length of their workday. Clyne noted that the lunches consisted of carbohydrate-rich foods that would nourish the miners during their long work days. The food in the pails consisted of slices of bread, cheese, eggs, salami, and even cottontail leg. In fact, according to Linda Wommack’s Women of the Colorado Mines, the women would make salami out of cottontail rabbits.

Figure 9 Coal miners with their lunch pails, Trinidad, Colorado.

Company town living was not extravagant, and any resource that the miners and their families obtained needed to be used sparingly to make it last. Clyne, who used oral histories to paint a picture of life in these company towns, shared Angela Tonso’s account:

“We used to buy ranch butter, you know, we bought it for 15 cents a pound. And we used to get a pail of lard….The butter we used sparsely for the toast, sometimes not even that…because [we had only] one pound a month for the whole family. But we used to use the lard instead, you know. And when we fry something, you know, we saved that…, especially a pork chop. Oh, my God, that was a luxury then. And we saved that grease, you know, pork chop grease to use it and use it.”

When families obtained pork chops, leftovers would be packed in the lunch pails as a rich and filling food option for the miners during their workday.

Our recipe today comes from Caroline Norton Trask’s The Rocky Mountain Cook Book published in 1903. Though there are extra flairs and ingredients that likely would not have been used in a coal mining company town, it serves as a good example of early 20th century pork chops.

Figure 10 Cover of Caroline Trask’s The Rocky Mountain Cook Book, first published in 1903.

We hope you enjoyed our brief history on coal mining, coal miners, and the railroad. In March, the Colorado Railroad Museum will be opening a new exhibit featuring coal mining and the railroads back from the early start featured here, all the way to the present day with a companion look at some of the related environmental effects. Keep an eye on our website for updates. If you try the recipes, let us know in the comments below, or on our social media pages.

Recipe

Rocky Mountain Cook Book Pork Chops

To fry or sauté them, have them cut one-half inch thick, dredge with a little flour, sage, salt and pepper, and cook until brown on both sides. It will take about twenty minutes. Serve on a hot platter, garnished with fried apples.

Rocky Mountain Cook Book Fried Apples

Cut slices of sour apples, one-half inch thick. Do not remove the skin. Sauté in beef drippings, pork fat or butter until tender.

Past Dining on the Rails Posts:

Dining on the Rails January 2025: Manhattan and Dining Car Bar Service

Dining on the Rails December 2024: Mincemeat Pie

Dining on the Rails November 2024: Prime Rib of Beef, Au Jus

Dining on the Rails October 2024: Huevos Rancheros and Traqueros

Dining on the Rails September 2024: Roulade of Beef

Dining OFF the Rails August 2024: Colorado’s Gold Rush and Hardtack

Dining on the Rails July 2024: Mary Engle Pennington and Union Pacific Chicken Salad

Dining OFF the Rails: Buffalo Bill, Delmonico’s, and Quail on Toast

Dining on the Rails: Oyster Pie and Olive Dennis

Dining on the Rails: Braised Rolled Calf’s Liver En Casserole and the Denver Zephyr

Dining on the Rails: Hashed Browned Potatoes and Potato Trains

Dining on the Rails: Champagne!

Railroad Hot Chocolate!

Pumpkin Pie!

Fred Harvey Coffee and Flank Steak

Roast Leg of Mutton

Mineral Water Lemonade

Roast Spring Lamb

Fruit Salad and Fruit Salad Dressing

Union Pacific Cole Slaw with Peppers

Bourbon Toddy

Cinnamon Toast and Children’s Menus

Harvey Girl Special Little Thin Orange Pancakes

Old Fashioned Navy Bean Soup

Apple Cider

Peach Cobbler

Barbeque

Mountain Trout

Eat like a Hobo!

Mother’s Day Shirred Eggs

How about a nice Old Fashioned?

French Toast, Anyone?

A Chocolatey Valentine’s Treat!

Western Pacific Pork Tenderloin

Cranberry Sauce

Oyster Stuffing!

Chicken Pot Pie

Chili

August 2021 – Pullman “Tom Collins” Cocktail

How about a salad?

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ham!

CRI&P’s New England Boiled Dinner

A Sweet Treat for your Valentine!

Black Eyed Peas!

Eggnog

Happy Thanksgiving!

Union Pacific Apple Pie

August 2020

July 2020

June 14, 2020

June 7, 2020

May 31, 2020

May 24, 2020

May 17, 2020

May 10, 2020

May 3, 2020

April 26, 2020

April 19, 2020

April 12, 2020