Happy Summer! And what a hot start to the season it has been. For this month’s posting of Dining on the Rails, we are going to feature Mary Engle Pennington and railroad car refrigeration to hopefully cool things down. We will also be sharing Union Pacific’s chicken salad recipe.

Figure 1 Mary Engle Pennington.

Mary Engle Pennington was born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1872. From an early age she had an interest in chemistry. In 1890, Pennington went to the University of Pennsylvania to obtain a higher education in science. The university at that time did not give women degrees, though Pennington was awarded a certificate of proficiency in chemistry, zoology, and botany. Pennigton continued her education and was granted a Ph.D. in Chemistry in 1895, at only 22 years old.

Figure 2 University of Pennsylvania, circa 1891.

After graduation, Pennington’s focus turned to food safety and bacteriology. In 1898 Pennington founded the Philadelphia Clinical Laboratory, and her research with bacteria led to new standards for preserving milk. In 1905, Pennington began working for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Bureau of Chemistry, which later became the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). She worked with Harvey Wiley, head of the USDA, and their work together led to the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act. After the act passed, Wiley asked Pennington to be the chief of the Bureau of Chemistry’s Food Research Lab. He submitted her resume under the name M.E. Pennington to hide the fact that she was a woman. When this was discovered, Wiley was able to fight for her to keep the position, and Pennington became the FDA’s first female lab chief. This lab learned that keeping food at low temperatures consistently kept the bacteria counts low, and thus, preserved food. Refrigeration became a crucial part of food safety.

Figure 3 Harvey Wiley, head of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

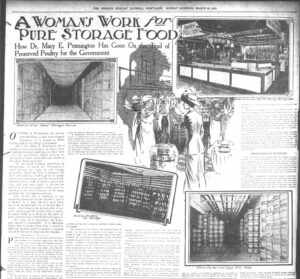

Of the many foods that Pennington studied, one that received a lot of attention was poultry. Author Chris Enns noted in her book Iron Women that housewives in 1910 were against purchasing frozen food as they didn’t consider it to be fresh. When they did purchase it, they were leaving chicken in a pan full of water outside to thaw, thereby ruining it and making those who ate it sick. The Oregon Sunday Journal published an article in March of 1910 about Mary Pennington and her work on poultry and food safety. The article notes:

“For some of its mischances the housewife herself is responsible. It is therefore fitting that, as women have done so much to afflict the modern supply of poultry, a woman should be the one to study out the remedies. Perhaps a mere man, not endowed with woman’s native affinity for chickens, might have been able to conduct the cold-storage investigation successfully, in spite of the handicap of his sex. But the fact is simply that mere man didn’t, and that Dr. Pennington’s previous record marked her for the expert whom Secretary Wilson and Dr. Wiley wanted on the job.”

So what does Mary Engle Pennington have to do with refrigeration on the railroad? Refrigerated boxcars were introduced to the railroads in the middle of the 19th century. These early designs used sawdust, animal hair, and sometimes dirt to insulate the refrigerated railroad cars. The ice itself was loaded into the top of the car and then the movement of the train would circulate the cold air in the earliest designs. These early designs weren’t very efficient, however. That’s where Mary Engle Pennington came in.

Figure 5 Mary Engle Pennington conducting tests on a refrigerated boxcar.

In her book Sisters of the Iron Road, author Shirley Burman notes that in World War I, Pennington was a consultant for the Perishable Products Division of the U.S. Food Administration. She traveled 60,000 miles per year in a lab car behind the refrigerated boxcars, or “reefers,” to test their efficiency. She found only 3,000 of the 40,000 government-owned refrigerated cars worked well (this was during the timeframe that the U.S. government took over control of the nation’s railroads during the War). While riding on these cars, Pennington suggested improvements that were then implemented. These improvements included thicker insulation and better circulation through the use of forced air in the cars.

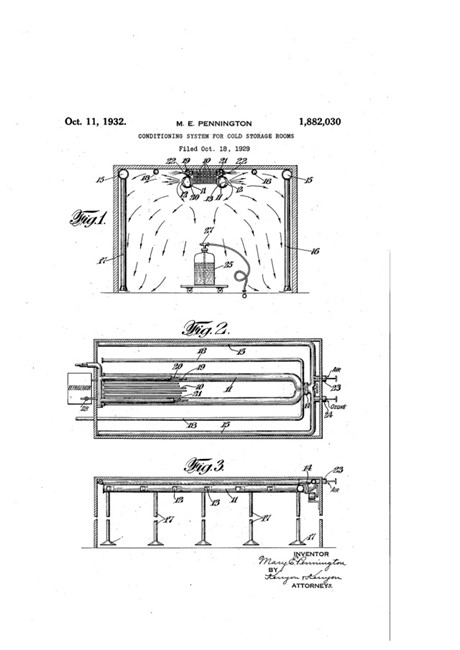

Figure 6 Pennington patent for conditioning system for cold storage rooms, 1932.

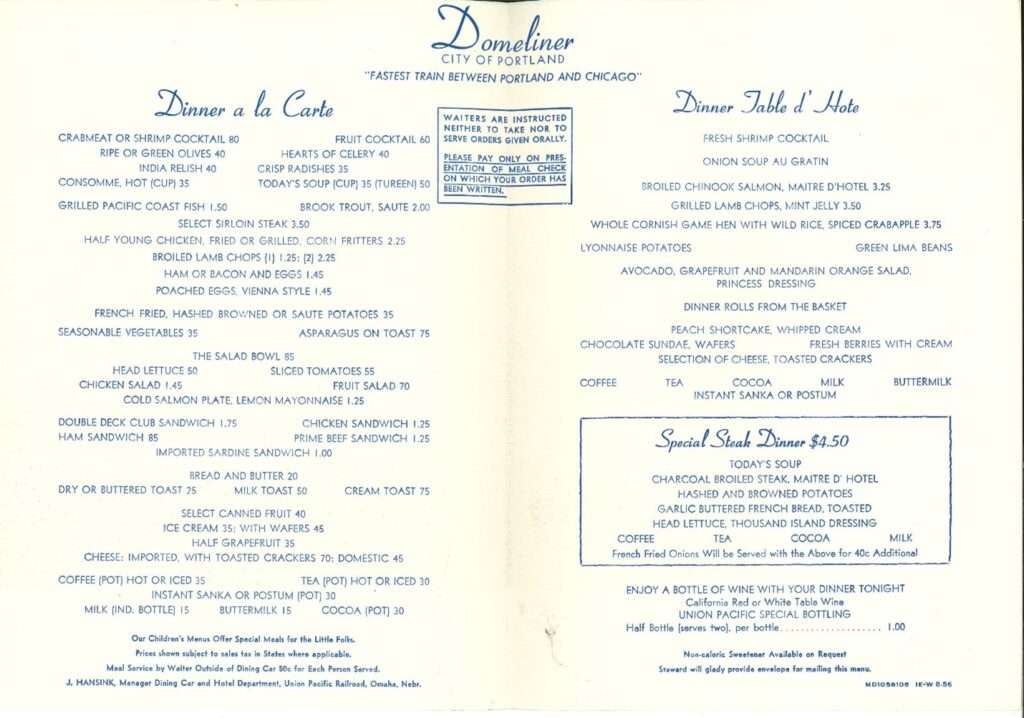

Better refrigeration systems on trains increased business. Enns noted in her book Iron Women, that the Union Pacific Railroad asked for bids for thirty-three thousand refrigerated boxcars in 1922. With updated “reefers,” railroads were able to transport butchered and dressed meat—rather than livestock—and the technology allowed dining cars on the trains to serve fresher food, such as chicken salad.

The history of chicken salad is a little difficult to track down. Most sources say that the first commercialized American version came about in 1863 when Liam Gray, owner of Town Meats in Rhode Island, mixed together leftover chicken with mayonnaise, grapes, and tarragon. It then became such a popular option that many meat markets also became delis. Earlier versions of chicken salad are found in early 19th century American cookbooks with slight variances in ingredients, but usually include cooked, cold chicken and mayonnaise.

Thank you for joining us on our brief history of Mary Engle Pennington, railroad car refrigeration, and chicken salad. Our recipe today comes from the Union Pacific Dining Car Cook Book and Service Instructions, published either in the late 1940s or early 1950s. If you do try the recipe, please let us know in the comments below or on any of our social media pages.

Figure 8 Union Pacific Dining Car Cookbook and Service Instructions in the Colorado Railroad Museum collection.

Union Pacific Chicken Salad

(To be made in kitchen) 2/3 cold boiled chicken white meat and 1/3 trimmed celery both cut in 1/4” dice. Season with salt and white pepper and moisten lightly with cider vinegar and oil. Sufficient quantity should be prepared in advance to take care of anticipated requirements and stored in refrigerator, otherwise to be prepared to order and served cold. When served, mix with sufficient mayonnaise to bind together. Mold each order carefully and top with a teaspoon of mayonnaise, two strips of pimento, 6 or 8 capers, 2 quarters hard boiled eggs, 2 slices dill pickle; sprig of parsley alongside.

PORTION—A la Carte: Pudding mold full

Table d’Hote: Pudding mold ¾ full

Past Dining on the Rails Posts:

Dining OFF the Rails: Buffalo Bill, Delmonico’s, and Quail on Toast

Dining on the Rails: Oyster Pie and Olive Dennis

Dining on the Rails: Braised Rolled Calf’s Liver En Casserole and the Denver Zephyr

Dining on the Rails: Hashed Browned Potatoes and Potato Trains

Dining on the Rails: Champagne!

Railroad Hot Chocolate!

Pumpkin Pie!

Fred Harvey Coffee and Flank Steak

Roast Leg of Mutton

Mineral Water Lemonade

Roast Spring Lamb

Fruit Salad and Fruit Salad Dressing

Union Pacific Cole Slaw with Peppers

Bourbon Toddy

Cinnamon Toast and Children’s Menus

Harvey Girl Special Little Thin Orange Pancakes

Old Fashioned Navy Bean Soup

Apple Cider

Peach Cobbler

Barbeque

Mountain Trout

Eat like a Hobo!

Mother’s Day Shirred Eggs

How about a nice Old Fashioned?

French Toast, Anyone?

A Chocolatey Valentine’s Treat!

Western Pacific Pork Tenderloin

Cranberry Sauce

Oyster Stuffing!

Chicken Pot Pie

Chili

August 2021 – Pullman “Tom Collins” Cocktail

How about a salad?

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ham!

CRI&P’s New England Boiled Dinner

A Sweet Treat for your Valentine!

Black Eyed Peas!

Eggnog

Happy Thanksgiving!

Union Pacific Apple Pie

August 2020

July 2020

June 14, 2020

June 7, 2020

May 31, 2020

May 24, 2020

May 17, 2020

May 10, 2020

May 3, 2020

April 26, 2020

April 19, 2020

April 12, 2020

0 Comments