Editor’s Note: While the hobo lifestyle may appeal to some of our readers, the Colorado Railroad Museum does not encourage anyone to try it. Trespassing on and around train tracks is very dangerous, and, like boarding freight trains, is illegal.

For this month’s posting, we’re exploring a different part of railroad culture—the hobo. While not an “official” part of railroad culture, hobos have a fairly long and sordid history in the United States. Still present today, hobos are people who travel on freight trains to find work. Generally, they are homeless by choice. Hobos are not to be confused with tramps, who hop trains but do not seek work, or bums who neither travel nor work.

Hobos emerged about the same time as the transcontinental railroad was completed, just after the Civil War. Prior to the railroad, there were certainly itinerant farm workers, but they were bound to specific regions by geography and lack of easy transportation. Due to their agrarian origins, some etymologists believe the word “hobo” comes from a combination of “hoe” and “boy.”

Once the railroad arrived, and the war ended, there was a large population of displaced people who needed work and were willing to do it for little pay—or maybe a meal or a warm place to sleep instead. The late 19th century brought about lots of opportunities to gain temporary work, from building the railroads to working in steel mills. As a result, from the late 19th century until the end of steam railroads is considered the heyday for the hobo.

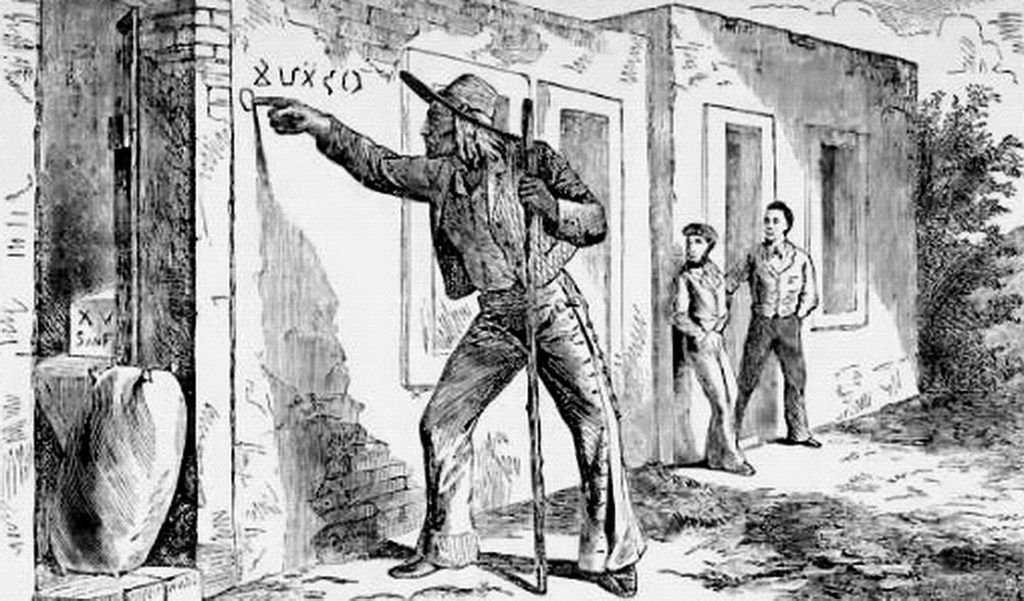

Chicago, due to its centralized location and the many railroads that converged in it, became a sort of hobo center by the end of the 1800s. Hobos could make a little money in the slaughterhouses and meatpacking plants before hopping a train to virtually any corner of the country to explore and find more work. Supposedly the Hobo Code was written in Chicago in 1894, however it has been very difficult to corroborate that.

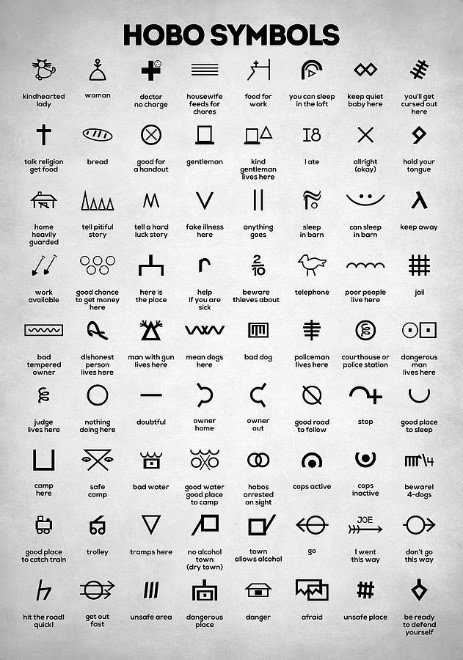

Somewhat disputed in terms of authenticity, the Hobo Code consists of graffiti symbols to help hobos communicate with one another, and find one another along the rails. For example, a sketch of a cat denoted that a kind lady lives nearby who might offer a free meal, whereas a series of parallel, horizontal lines meant a housewife would feed you if you did chores for her.

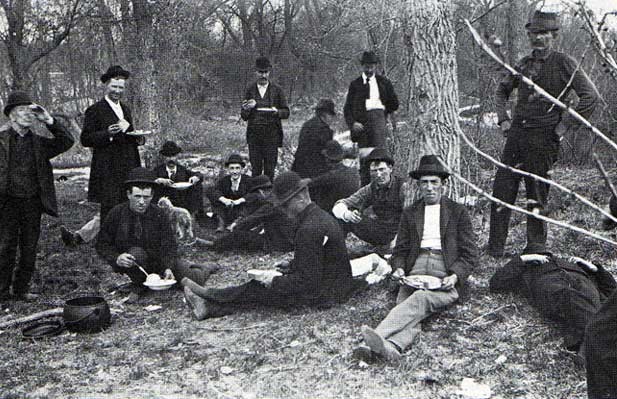

Some hobo historians claim that the Hobo Code was used to let others know where to find the nearest “jungle” or hobo encampment. While it may seem like a lonely lifestyle, there is actually a strong kinship associated with hobo jungles. Food in the jungles was made by the whole group, and while it was nothing fancy, it was very communal. Whatever each hobo had went into a pot of stew shared by the whole jungle. Perhaps one hobo acquired a few carrots from a charitable person, while another stole an onion off a box car, while another had a few potatoes from a farm he worked on briefly… From this concoction, a “hobo stew,” also known as “Mulligan/Mulligatawney stew” was born and became the traditional food of the hobo.

Today’s hobos are in it for the freedom to explore, although being a hobo in the 21st century, especially after 9/11, is far more complicated than it was 100 years ago. History shows that ridership increases when the economy is poor, such as it did after the Civil War, after World War I, and all through the Great Depression. A testament to the existence of the hobo lifestyle in the 21st century is the National Hobo Convention, which will happen in Britt, Iowa in August of 2022. This is the 122nd year of the convention, at which hobos and their families will gather to memorialize hobos of the past, name a hobo king and queen, share stories, and share food (including Mulligan stew).

Many famous people were hobos at one point in their life, including boxer Jack Dempsey, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas (who supposedly hoboed his way across the country to attend law school), and famous writers Louis L’Amour and Jack London. One can only imagine how hopping trains, or in hobo-speak, “catching out,” colored their lives and wound up in their stories.

A colorful lifestyle indeed, being a hobo is not easy. Establishing roots is certainly very hard, yet that seems to be the hobo creed:

Everything I’ve owned, and everything I want in life, fits in this house [points to his knapsack], right in my pack. Anything that doesn’t fit in my pack, I can’t carry with me. I don’t want it. I can’t have it. It all gets left behind. It makes me a different kind of person. It’s given me something special in life. I’m not attached to anything. I wander with the winds. I know that a lot of people wish they could do the same.

-Hobo known as “The Dutchman,” 2018

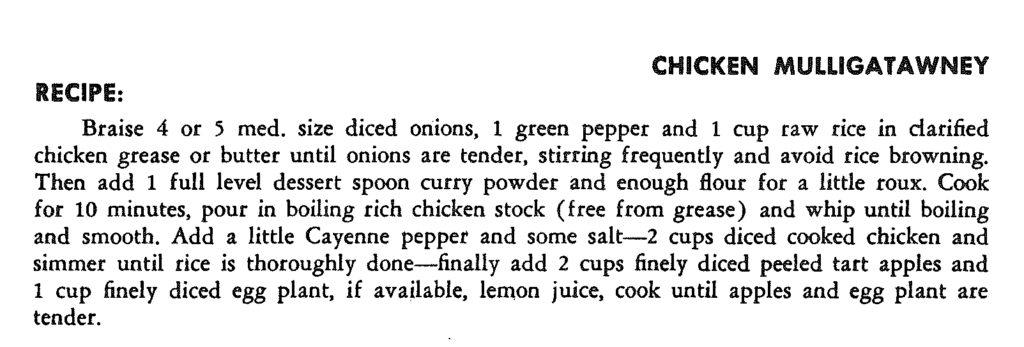

Perhaps you’d like to try your own form of Hobo/Mulligan stew. Although no written hobo recipes exist, the Union Pacific Railroad had a recipe for it, which we have shared below. If you have a family recipe for Mulligan stew, or if you have hobo heritage, please feel free to share your story and/or recipe in the comments, or via our Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter pages.

Figure 6 Union Pacific Chicken Mulligatawney soup. From Union Pacific Dining Car Instructions, Colorado Railroad Museum collection.

Mulligan Stew (from: https://www.smalltownwoman.com/mulligan-stew/)

INGREDIENTS

- ⅓ cup all-purpose flour

- ½ teaspoon onion powder

- ½ teaspoon garlic powder

- ¼ teaspoon fresh ground pepper

- 1 lb beef stew meat

- 2 tablespoons vegetable oil

- 1 medium onion chopped

- 2 cups low sodium beef broth

- ½ teaspoon dried oregano

- ¼ teaspoon dried basil

- ¼ teaspoon dried marjoram

- 2 medium gold potatoes cubed

- 1 bag (19 ounce) frozen mixed vegetables (corn, carrots, peas and green beans)

INSTRUCTIONS

- Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

- Add flour, onion powder, and garlic powder and freshly ground black pepper to a large zipper seal bag and shake to combine. Add beef stew meat and shake to coat. Heat 1 tablespoon vegetable oil in a Dutch oven over medium heat. Using tongs remove the beef and add to the pan. Reserve any flour mixture left in the bag. Brown beef on all sides; removing to plate when complete.

- Add 1 tablespoon vegetable oil to the Dutch oven over medium heat. Add chopped onion and cook 3-4 minutes. Sprinkle in remaining flour (1 1/2 tablespoons) and cook for 2 minutes; stirring constantly. Add oregano, basil and marjoram; cook for 30 seconds stirring continuously. Stir in beef broth; cook for 2 minutes stirring several times. Add the browned beef back to the pan. Cover and place in the oven for 1 hour.

Add potatoes, corn, carrots, peas and green beans to the pot. Place back in the oven and cook for an additional 30 minutes or until stew and vegetables are tender.

Past Dining on the Rails Posts:

Dining on the Rails: May 2022 – Mother’s Day Shirred Eggs

Dining on the Rails: April 2022 – How about a nice Old Fashioned?

Dining on the Rails: March 2022 – French Toast, Anyone?

Dining on the Rails: February 2022 – A Chocolatey Valentine’s Treat!

Dining on the Rails: January 2022 – Western Pacific Pork Tenderloin

Dining on the Rails: December 2021 – Cranberry Sauce

Dining on the Rails: November 2021 – Oyster Stuffing!

Dining on the Rails: October 2021 – Chicken Pot Pie

Dining on the Rails: September 2021 – Chili

Dining on the Rails: August 2021 – Pullman “Tom Collins” Cocktail

Dining on the Rails: June – How about a salad?

Dining on the Rails – Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ham!

Dining on the Rails: CRI&P’s New England Boiled Dinner

Dining on the Rails: A Sweet Treat for your Valentine!

Dining on the Rails: Black Eyed Peas!

Dining on the Rails: Eggnog

Dining on the Rails: Happy Thanksgiving!

Dining on the Rails: Union Pacific Apple Pie

Dining on the Rails, August 2020

Dining on the Rails, July 2020

Dining on the Rails, June 14, 2020

Dining on the Rails, June 7, 2020

Dining on the Rails, May 31, 2020

Dining on the Rails, May 24, 2020

Dining on the Rails, May 17, 2020

Dining on the Rails, May 10, 2020

Dining on the Rails, May 3, 2020

Dining on the Rails, April 26, 2020

Dining on the Rails, April 19, 2020

Dining on the Rails, April 12, 2020

0 Comments